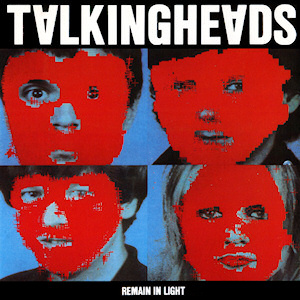

Remain In Light – Talking Heads (1980)

September 20, 2024

To me, Remain in Light is the centerpiece in one of the best three-album runs for any rock band in history. Sandwiched between 1979’s Fear of Music and 1983’s Speaking in Tongues, this album reflects the genius of Talking Heads at the absolute peak of their powers. The third consecutive album in their discography produced by Brian Eno demonstrates the band’s ability to effectively create their own unique style of music that could impress the snootiest of music critics while also charting on the Billboard 200. As was the case with Bryan Ferry on Roxy Music’s records of the early ’70s, the album gets a lot of its juice from the combination of an eccentric, dynamic front man in David Byrne partnering with the musical mad scientist in Eno to produce an abstract, but accessible sound. Eno and Byrne had just come off of recording My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (an equally impressive album, although far less commercially viable), and were inspired by the Afrobeat sounds perfected by Nigerian musician, Fela Kuti, as well as the growing influence of hip-hop in the United States. By looping individual instrumental recordings by the Heads and a roster of studio musicians, including Adrian Belew on guitar and Robert Palmer on percussion, the duo was able to perfect what was later described by Byrne as the creation of “human samplers.”

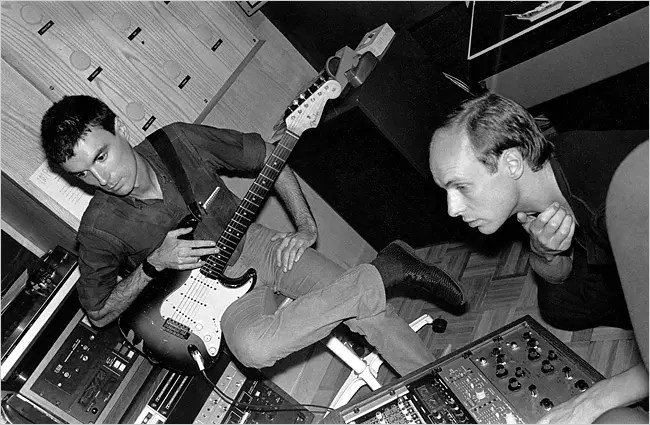

David Byrne and Brian Eno recording in studio

Although the musical results would ultimately speak for themselves, the increasingly closed-off collaboration between Byrne and Eno caused friction with the rest of the band, with Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz often no-showing studio recording sessions. Things became so fraught that after hearing that Eno wanted to be included on the album’s cover, Weymouth suggested superimposing his face over portraits of the four band members as a shot at his inflated ego and growing influence on the recordings. The internal strife reached its pinnacle after the album was released – with Weymouth, Frantz, and Jerry Harrison discovering that Byrne and Eno had had listed the songwriting credits as “all songs written by David Byrne & Brian Eno (except ‘Houses In Motion’ and ‘The Overload,’ written by David Byrne, Brian Eno & Jerry Harrison).” Later editions of the album would credit songwriting to all members of the band, but the damage had been done by that point and would prove critical in the ultimate dissolution of the band years later. (Author’s Note: I saw a screening of “ Stop Making Sense” followed by a Q&A with the band in Brooklyn in June 2024, and was lucky enough to have them select my question – “What did you learn from working with Brian Eno?” Upon hearing the question, Weymouth immediately stared daggers into Byrne’s soul – leading him to respond, “Did you see the look she just gave me?”, and prompting nervous laughter from the audience. I will go to my grave knowing that I fanned the flames of resentment within one of the greatest bands of all time.)

Despite the drama behind the scenes, this no-skip masterpiece features some of the best songs of the entire Talking Heads catalog. Aside from the genre-blending impact of the music, which successfully merges the Afrobeat influences with the popular new wave and post-punk sounds that had gained increasing popularity in the US and UK in the late ’70s, Byrne’s lyrics take aim at many of the political and cultural issues of the time. “Born Under Punches” focuses on the post-Watergate distrust of “the hands of a government man,” while “Listening Winds” tells the story of Mojique, who is disgusted by the droves of American colonists in his homeland and decides to “drive them away” through a terrorist attack where he “plants devices through the Free Trade Zone.” We also hear Byrne’s thoughts on an increasingly self-involved, appearance-obsessed society, including the “large automobiles” and “beautiful homes” of “Once in a Lifetime,” as well as the hyper-fixation on achieving the “ideal facial structure” in “Seen and Not Seen.” The album concludes with “The Overload,” the lyrics of which are made up entirely of things the music press wrote about Joy Division. Despite the fact that none of the members of Talking Heads had ever heard Joy Division, they used these descriptions to imagine what a Joy Division song might sound like – and actually come pretty close.

Jerry Harrison, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and David Byrne

As was the case with Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, Remain in Light proves that dysfunction and animosity among band mates can lead to the highest levels of achievement. Byrne, Eno, and company were able to create what can be viewed as a “cool kid” parallel to Paul Simon’s Graceland and introduce Western audiences to a well established genre of African music. Although some may criticize Byrne (and later Simon) of cultural appropriation, I’ve always found that argument to be reactionary and misplaced. To me, it’s a positive to introduce Western audiences to genres and artists they had never heard before. Had I never fallen in love with Remain in Light, I never would have discovered Kuti or his fantastic run of albums from the 1970s. Artists are supposed to be inspired by other artists, and as long as the past is expanded upon and not simply stolen, it broadens the music landscape and gives better historical context to its listeners. Remain in Light makes you dance, makes you think, and makes you feel alive. It inspires you to listen to more music to chase the buzz that it gives you from the first song to the last. It is undoubtedly the high point of an excellent Talking Heads discography, and one of the great musical achievements of the 1980s.

Leave a reply to Law and Order – Lindsey Buckingham (1981) – 80 Albums of the 80s Cancel reply