Graceland – Paul Simon (1986)

December 5, 2025

Prior to the release of Graceland, Paul Simon had established himself as one of the preeminent American pop music acts, with a prolific discography that included five albums as part of Simon & Garfunkel, plus an additional six as a solo artist. But Simon had seen his star begin to wane as he entered the 80s, failing to achieve his usual levels of commercial success with his most recent album, Hearts and Bone (1983). And on top of the major dip in his career trajectory, he found himself at an all-time low in his personal life as well, as both his working relationship with Art Garfunkel and his marriage to Carrie Fisher had fallen apart in the prior few years.

But in 1984 – amidst a period of severe depression – Simon agreed to produce a record for a young artist named Heidi Berg, who had previously played in the house band for Saturday Night Live. During their early meetings, Berg shared a bootleg cassette with him that contained mbaqanga – which was a type of black street music from Johannesburg – and immediately sparked feelings of happiness and musical inspiration in Simon and would pave the way for an unexpected twist in his career (and end up being a really tough beat for Berg, who was understandably upset that he lifted the concept for her album).

Understanding that this music had been completely unfamiliar to him up until this point, Simon felt that the only way he could truly pursue this creative direction would be to go Johannesburg and work with local musicians – a plan that was complicated by the UN cultural boycott against Apartheid-era South Africa, which had been in effect since 1980. So during his work on the “We Are the World” single, he approached producers Quincy Jones and Harry Belafonte to get their thoughts, and ultimately received their encouragement to move forward with the project. Simon also got the stamp of approval from the South African black musicians’ union, given the fact that they believed it would expose Western audiences to African music.

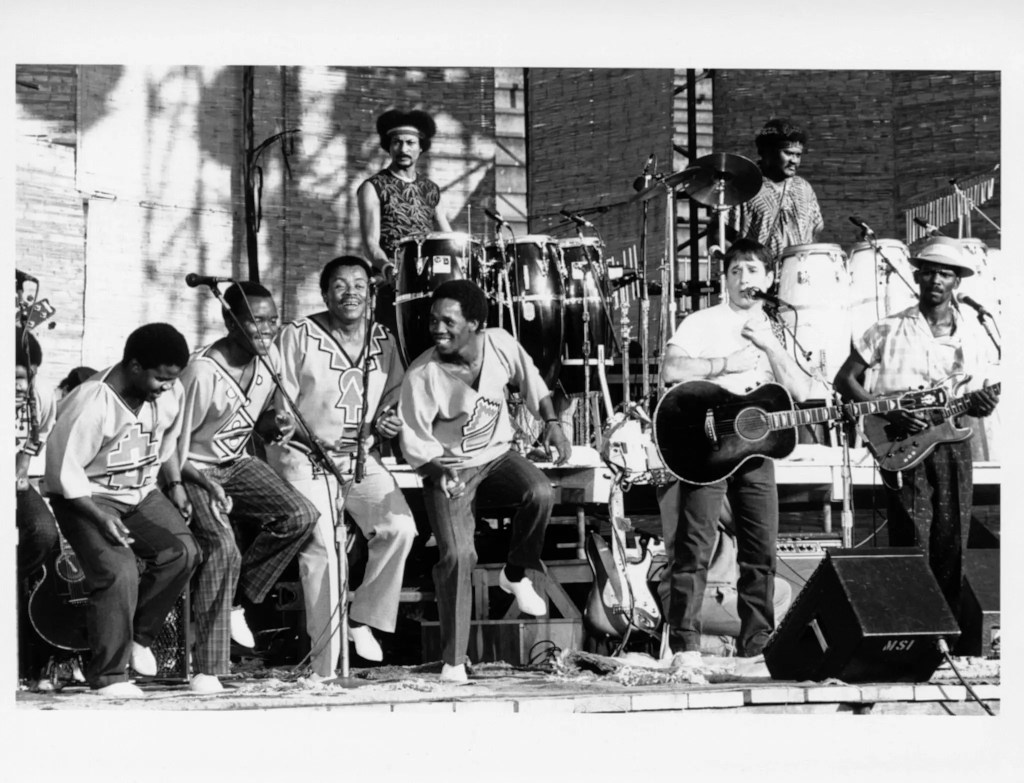

Paul Simon with Ladysmith Black Mambazo

So despite receiving a lot of flack from critics – who accused him of breaking the boycott and of cultural appropriation – Simon would head down to Johannesburg in 1985. Aside from his completely valid arguments that he would not be doing any work for the South African government, nor would he be playing for segregated audiences; Simon also used the opportunity to showcase local musicians on an international stage and demonstrate collaboration between black and white artists as a positive thing for culture. And on top of these compelling counterpoints to his harshest critics, he provided all collaborators with royalties from album sales and paid them $200 per hour for their work (and for context – the standard hourly rate for top studio musicians at the time was $15 in Johannesburg and $70 in New York City).

Even after his trip to South Africa had concluded, the controversy continued for Simon, who had come back to New York to add vocals and do additional work on the tracks he had recorded while in Johannesburg. He brought in a number of artists to help him add the finishing touches to his upcoming album, including Linda Ronstadt, Los Lobos, and Rockin’ Dopsie & the Zydeco Twisters – all of whom added further complications to an already deeply muddy situation. Ronstadt had come under fire for playing at a white luxury resort in South Africa three years prior, while Los Lobos and Rockin’ Dopsie & the Zydeco Twisters both alleged Simon had plagiarized their work without proper compensation.

But in spite of all of the drama and allegations, Graceland would go on to reach huge commercial success (peaking at #3 on the Billboard 200), receive enormous critical praise, and become one of the most beloved albums of the entire decade. The songs perfectly blend the upbeat, fun street music vibe of its originators with the signature Simon sound that had become an established slice of Americana over the prior twenty years. His always brilliant lyrics shine when they’re at their most personal, including multiple allusions to his divorce from Carrie Fisher – none of which is better than the title track’s lyric, “Losing love is like a window in your heart; everybody sees you’re blown apart” (the end of which could just as easily be heard as “your blown up heart”). He dives into other seemingly autobiographical moments throughout the record, with stories of New York City social climbers (“I Know What I Know”), an anecdote about having someone at a party not know his or his first wife’s name (“You Can Call Me Al”), the struggles of going through a divorce with another A-list celebrity (“Crazy Love, Vol. II”), and a conversation with his son about his life before becoming a father (“That Was Your Mother”). And Simon also makes a point to hit upon some of the sociopolitical observations he made during his time in Johannesburg, with lyrics about starvation and terrorism on “The Boy in the Bubble,” intense levels of poverty on “Homeless,” and the lasting impact of colonialism and war on “All Around the World or the Myth of Fingerprints.”

Simon and Chevy Chase perform “You Can Call Me Al” at a benefit concert in ’87.

Graceland maintains one of the most complicated legacies of any piece of pop music to be released in the last century. On one side – beloved as the revival of an extraordinary career, a masterclass in lyricism and composition, a celebration of international music, and an introduction of unfamiliar artists to Western audiences. But on the other – it is reviled as an example of cultural appropriation, plagiarism, and putting profits over politics. As I’m sure is clear throughout this piece, my opinion is most certainly with the former, and I consider the latter’s arguments to not only be in bad faith, but also completely removed from the facts of the situation. Much like many of the criticisms of Talking Heads’ Remain in Light and Mick Fleetwood’s The Visitor – the idea that spotlighting the excellent music of other cultures is a bad thing is just asinine. The entire point of art is to be inspired by things you’ve seen or heard, and then use them as templates on which to make your mark with your own talent and vision. Graceland was not a sneaky ripoff of other artists in pursuit of fame and fortune (Simon clearly had plenty of each) – it was a love letter to a largely unknown genre of music, a tribute to international musicians, and ultimately a gift to Western audiences who otherwise may never have been exposed to such beautiful and high-quality art.

Leave a comment